America loves to follow along with salacious and scandalous court cases. From the OJ Simpson murder trial to the coverage granted to serial killers like Ted Bundy and John Wayne Gacy, Americans consume true crime content like nothing else. In the modern era, that viewership has only seemed to increase. Casey Anthony, JonBenet Ramsey, Gabby Petito, Alex Murdaugh, and most recently the University of Idaho murders have all shot to the top of headlines and the front of minds across the country.

The most shocking cases make worldwide headlines. Viewers frantically follow every unearthed police affidavit and track each courtroom development. Trials become the site of pandemonium, as people across the country check in each day for updates from the prosecution and defense.

It all had to start somewhere, right? As we’ve previously covered, historians now note the “true crime” trend launched nearly 200 years ago with a sensational murder trial set in New York City. But that wasn’t the first modern-style murder trial in American history. In fact, the United States’ first-ever recorded murder case took place three decades before, in 1800.

The incident was a grisly killing that took place just before Christmas in 1799. The victim was a pretty young woman dead-set on eloping with who she thought was to be her future husband. The alleged assailant was a well-connected man who denied having killed his would-be bride. And the lawyers involved would go on to become two of the most famous men in early American history. In this list today, you’ll learn the shocking truth behind America’s first-ever recorded murder trial.

Related: 10 Most Disturbing Moments During Ted Bundy’s Trials

10 The Background

Levi Weeks was a young man working as a carpenter in New York City in the 1790s. He wasn’t particularly successful in his own right, but his brother Ezra had become wealthy. Ezra was a builder involved in many notable early NYC projects that helped develop the city as a bustling port and economic center. So Levi was hoping to ride his brother’s connections to a worthwhile position in society on his own.

By 1799, he was plying his trade with his hands while working closely with his influential brother. Levi wanted to become an architect one day and was planning on studying more for the role. But suddenly, love got in the way—and by the end of 1799, he was said to be smitten with a young woman in town.

The woman’s name was Gulielma Sands, although everybody called her Elma. She had just moved to New York City earlier in 1799 when she met Weeks. It all came about because Elma came to town to work for her cousin, Catherine Ring, and Catherine’s husband, Elias. Those two owned a millinery business and a boarding house. They put Elma up in the boarding house once she arrived in town. As it turned out, Levi was staying in that very same boarding house.

The two quickly struck up a connection. For a while, they kept their love affair hidden, but other boarders soon found out. On at least two occasions, Levi and Elma were caught having sex in the rooming house—a scandalous occurrence at the time for two unmarried partners. Soon, the stage was set for them to elope. Levi was to make an “honest woman,” as it were, out of Elma. Until things went terribly, terribly wrong…[1]

9 The Murder

Just days before Christmas 1799, Sands and Weeks reportedly hatched a plan to run off together and get married. On December 22, Elma told her cousin Hope Sands—who was also a resident of the Rings’ boarding house at the time—that she and Levi were going to run away together that night and get married. Elma and Levi were engaged, the hopeful young woman explained to her cousin, and they were going to start a new life together.

That evening, both Elma and Levi left their rooms at different times, according to witnesses in the house. But when Levi later returned alone hours later, other tenants thought it strange. Sands never came home that night. In fact, she was never seen alive again. Christmas went by and the New Year came, and nobody had any idea where she’d gone.

Boarders reported the bizarre and uncharacteristic disturbance to detectives in New York City. The cops got on the case quickly by the very start of the New Year. They interviewed Weeks about Sands’s whereabouts after learning the story of their supposed engagement. Levi denied having any knowledge about it, though. Instead, he claimed, he and Sands had never been engaged. What’s more, the wannabe architect asserted that he was never with Elma on the night of her disappearance.

Cops were skeptical, but they had little to go on. By the time their investigation began, they hadn’t found a body or other definitive proof that Sands had met harm. So they kept the file open and kept searching, but they were unable to arrest Levi or anyone else. Still, suspicion grew. And days after the detective work began, a terrible discovery would change the course of history.[2]

8 The Body

From the very start, Catherine and Elias Ring didn’t believe Levi’s claims of ignorance. They were concerned about their missing loved one and worried she had met harm at Weeks’s hand. So they went to reporters to drum up attention about the situation. They offered details of Elma’s disappearance and made claims about their belief she’d been killed.

Newspaper reporters ate up the story and began publishing pieces on it. Quickly, all of New York was reading about the mystery behind Elma Sands’s disappearance. And after days of uncertainty, the Rings got what they wanted: some answers in the form of hard evidence.

At first, it was a small sign. Days after Christmas, a little boy playing in a New York park found a small piece of ripped clothing. The cloth belonged to a very unique outfit belonging to Elma Sands. Suddenly, the Rings—and the authorities—had some kind of sign about where she’d vanished. Then, on January 2, 1800, Sands’s body was found. Passersby discovered her lifeless corpse lying inside the Manhattan Well.

Her body was lifted out, and her identity was confirmed. Then, the body was taken to the Rings’ boarding house. There, it was left on public display for three days. That morbid detail may shock our modern sensibilities, but it did something very important at the time: It made Elma seem real to New Yorkers who came by to view the body. She was seen as a vulnerable and hopeful young woman in love who became the victim of a horrible crime. Soon, public outcry reached unprecedented levels.[3]

7 The Outcry

Almost immediately, the newspapers drummed up a public outcry, and New Yorkers largely assumed Weeks was guilty. There had been no trial—there hadn’t even been an arrest amid the earliest of the callouts—but Levi was suddenly a marked man in NYC. Cops arrested him and charged him with murder as journalists all but declared him to be guilty of the awful crime.

Seemingly overnight, the murder became a true crime sensation that divided New Yorkers who followed along with the case. Weeks quickly knew he had to build a significant defense to avoid a proverbial (or possibly literal) public lynching. So he turned to his brother Ezra for help in the matter.

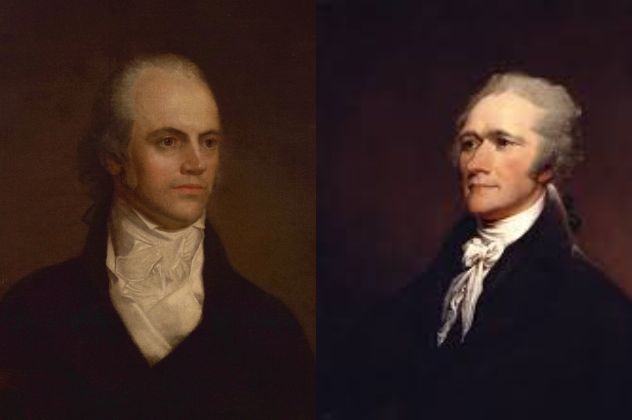

As we’ve already learned, Ezra was wealthy and influential around the Big Apple. Even though Levi hadn’t attained career success, Ezra was well-known and well-liked. More importantly, he was well-connected. In fact, Ezra was such a part of the elite New York social scene that he was able to bring together bitter rivals for a common cause. The builder and architect went to Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr—two of America’s most famous and most vicious political rivals at the time—with a request to defend his accused brother.

Despite deeply distrusting each other’s politics, Hamilton and Burr both signed on to defend Levi in court. And yet neither one had much experience with criminal law. So Ezra hired a third Founding Father to defend Levi as well: Henry Brockholst Livingston. Of the three, Livingston was a veteran criminal attorney and defense lawyer who was very respected in New York legal circles. Suddenly, the accused murderer had a dream legal team backing him just as public outcry reached a fever pitch.[4]

6 The Rivals

The rivalry between Hamiton and Burr is infamous by our modern standards. But at the time, their uneasy truce to help each other on a criminal case like this was nearly unheard of. The famous political duo’s bitter distrust for each other began nearly a full decade before, in 1791.

That year, Hamilton was elected to a U.S. Senate seat, defeating Burr’s father-in-law in a hotly-contested campaign. Hamilton and Burr had directly opposing political ideologies, too. Hamilton was a strong supporter of the Federalist Party. Burr, on the other hand, supported the more laissez-faire Democratic-Republican Party.

In Hamilton’s mind, the purpose of government was to produce a powerful central establishment overseeing the new nation. Burr felt strongly about the ideals of men like Thomas Jefferson, who believed states’ rights were key to allowing each separate entity to govern itself. While Hamilton argued for greater commerce in cities and more oversight into developing what would soon become the world’s most powerful country, Burr wanted to push an agrarian, localized, and communal society onto Americans.

The two lawyers would debate and fight over their differences for years. Not long after this murder trial, of course, their disagreement would reach a fatal conclusion. But for now, they allied behind Levi Weeks. Along with Livingston, their goal was singular: acquit the accused killer as quickly and fully as possible.[5]

5 The Defense

Even before the trial began later in 1800, Levi Weeks was facing an uphill battle. Hamilton, Burr, and Livingston may have been brilliant lawyers and smart men, but their client was hated all across New York. The three lawyers were forced to consider unique arguments to get their client off the hook. Even then, the possibility of an already-influenced jury pool weighed heavily in the minds of the three attorneys.

Plus, Weeks’s alibi on the night Elma went missing was weak. He had no witnesses to attest to where he’d supposedly gone that evening, and he had few character witnesses who would speak up in his name—although his well-connected brother Ezra did give it a shot.

As for the prosecution, they played up the trial’s notoriety to their advantage. Prosecutors claimed Levi had seduced Elma with phony promises to marry her. In actuality, they claimed, he never intended to marry the young woman. Instead, he wanted to use her for a sexual relationship before casting her aside. Then, when things got too risky by late December, prosecutors argued, Levi simply killed Elma to rid himself of the responsibility.

The team gunning for Levi’s conviction even went so far as to argue Sands had been pregnant at the time, and murder was Weeks’s way out of that responsibility. The lurid nature of those claims of premarital sex served to shock the jury. They also cast scorn on Levi from many New Yorkers who followed the case closely in the papers.[6]

4 The Trial

At the trial, prosecutors called a man named Richard Croucher to the stand. He was their star witness, and for a good reason: he claimed he personally saw Elma and Levi in sexual relations. Croucher also claimed Levi had been trying to get out of the affair at the time of Elma’s death.

His testimony cast Weeks in a decidedly negative light. It also put the jury’s attention on Levi as a playboy and a conman. The moral underpinnings of the time made it so that those traits would shock jurors. Prosecutors were hoping for just that, and Croucher’s supposed insider knowledge of what really went on in the boarding house proved powerful.

But Hamilton and Burr had their own tactics too. For one, the defense was able to prove Sands was not pregnant at the time of her death, as the prosecution had claimed. Furthermore, the defense team took the offensive and attacked Croucher personally. Hamilton and Burr claimed it was actually Richard who had been having an affair with Elma and not Levi. Then, Weeks’s defense attorneys brought a witness to the stand who testified they actually saw Croucher near the Manhattan Well on the night of Elma’s disappearance, and not Weeks.

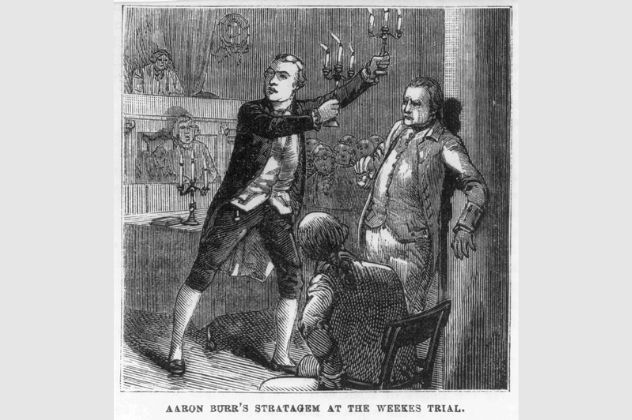

The cross-examination concluded in a flourish when Hamilton faced down Croucher, who was giving testimony. According to the new 223-year-old court transcript, Hamilton shoved two lit candles in front of Croucher’s face and yelled at the jury: “Mark every muscle of his face! Every motion of his eye! I conjure you to look through that man’s countenance to his conscience!”[7]

3 The Verdict

Hamilton’s courtroom theatrics worked. And the chaos and marathon trial time helped Weeks, too. At that time in American history, most trials only lasted one day. Even for high-profile cases, court proceedings were largely confined to a single working day before a verdict was rendered. In Levi’s case, the trial reportedly droned on for 44 consecutive hours without a break. Testimony and witness statements were added one on top of another, exhausting the jury, judge, and each legal team.

In fact, reports from the time indicate one of the prosecutors actually fell asleep at his table in court during the final hours of the trial. Then, when it came time to mount a closing statement, he supposedly couldn’t provide one. True or not, that legend speaks to how physically and emotionally demanding the shocking trial had become.

But after the countless hours of work leading up to the courtroom showdown and the 44 grueling hours on the record, it all ended quickly. The defense team had grown very confident in their case by the end of it all. After the prosecutor couldn’t be roused from slumber, it was Hamilton’s turn to offer a closing argument in Levi’s defense. He chose not to do so, either. He and Burr believed they had made such a strong case that they didn’t need one. And as it turned out, they were right.

After only five minutes of deliberation, the jury came back with a verdict of not guilty. Levi Weeks was off the hook in the murder case, and immediately, he was a free man. Unshackled from the murder charges that had been following him around since the end of 1799, he rushed out of court and back into his old life. Hamilton and Burr, already famous across America, rose to new heights after their successful defense of their client in the shocking and sordid affair.[8]

2 The Aftermath

Suddenly, Levi Weeks was a free man again. He was acquitted of the murder charge and officially—at least in the eyes of the law—not the person who killed Elma Sands. But his public reputation was tarnished forever. New Yorkers still saw him in a negative light. In that era, and in high-end circles, reputation was social currency. With Levi wanting to become a powerful builder and architect in town, his reputation meant everything. With it destroyed for good, he was forced to flee town and avoid endless public criticism.

So he settled in Natchez, Mississippi. There, he became the architect he’d always hoped to be. He married a well-to-do woman from a notable local family, and they had four children together. He designed and built several notable buildings in Natchez and along the Mississippi River. For the next two decades, he lived there with his family. In 1819, at the age of 43, he died. Levi Weeks’s memory lives on in Natchez, though. A house designed by Weeks—the city’s Auburn Mansion—has since become a National Historic Landmark.

As for Elma Sands’s real killer, no one else was ever arrested or charged with the crime. Interestingly, the prosecution’s star witness may have made a good suspect himself. Richard Croucher, the man who accused Levi of killing Elma after claiming to have witnessed their illicit affair, was later implicated in a series of other awful crimes. At one point, he was arrested for raping his teenage stepdaughter. He was tried for that crime and found guilty. Not long after, though, he was pardoned for mental health reasons.

Upon his release, Croucher moved back to England. Records become spotty at the end of his sordid life, but historians now believe he was executed for another grisly crime of some sort. Whether or not he was responsible for Elma’s murder, Croucher’s own dark side seems to have eventually caught up with him.[9]

1 The Famous Fate

While Weeks and Croucher slowly faded into their more anonymous futures, Burr and Hamilton quickly became two of America’s most followed men. Later in 1800, Burr joined up as Thomas Jefferson’s running mate in that year’s presidential campaign. Because of how elections worked at the time, party-line tickets weren’t the same. The candidate with the most electoral votes became president, while the one in second place became vice president.

So that fall, Jefferson and Burr tied in the initial voting. Burr moved hard to become president in a run-off vote. But Hamilton, who had long disagreed with Burr on a variety of political issues, begged his Federalist Party pals to throw their votes behind Jefferson. The party did as Hamilton requested, Jefferson won the run-off vote, and Burr was left angered over it.

Four years later, after further political disagreements, Hamilton and Burr opted to end it all with a public duel. Each man agreed to the terms of the duel, and on the fateful day, each man took shots at the other. Hamilton’s bullet missed the mark, but Burr struck a direct hit. For a while, Hamilton remained alive, but it was clear he’d been seriously wounded.

About 36 hours after the duel, he died at his home. Burr—like Weeks four years before him—became considerably ostracized among America’s shocked political elite. The rest of that story, as we now know, is history. But as it turned out, these two bitter foes worked closely together to draw an acquittal just a few years before in the first-ever recorded murder trial in the history of the United States.[10]